Research magazine of the University of Regensburg

Karate: It's fun, not immoral, and doesn't make you fat!

Katharina Dahmen-Zimmer and Petra Jansen

Even though exercise can no longer be naturally integrated into our lives today, its importance for maintaining cognitive, emotional, and physical health is increasingly recognized, especially for the elderly. In three studies, we investigated the effect of karate on healthy aging and on patients with Parkinson's disease. Karate was selected as a sport that combines both cognitive and motor elements. All three studies showed that karate (trained according to the rules of the German Karate Association) is easy to practice in old age and even with a movement disorder. Individual positive, statistically significant effects were demonstrated, for example, with regard to cognitive processing speed and balance. Initial work is promising, but research in this area is caught in the tension between scientific rigor and feasibility. Collaboration between physicians, sports scientists, psychologists, and computer scientists is desirable for this promising field of research.

Humans are evolved to move. Hippocrates (c. 460 BC to 375 BC) already pointed out that physical activity is not only essential for survival, but can also be considered healing. But even movement is adapting to the changing times and can no longer be naturally integrated into our lives. While just a few generations ago, people walked several kilometers a day on average, today, in our culture, locomotion on wheels is the norm and not, as it once was, reserved for only a few privileged individuals. Nevertheless, the importance of movement is once again being increasingly recognized – among younger people perhaps more for acquiring a fit appearance, among the older population for maintaining cognitive, emotional and physical health. This is where our research comes in: How can exercise be designed so that it can contribute to holistic health in old age?

Exercise or sport – do they equally promote holistic health in old age?

The term "exercise" refers to any kind of physical activity. The difficulty in finding a precise definition of the term "sport" probably lies in its broad use and perception: Perceptions range from competitive sports to rehabilitation sports, health sports, company sports, recreational sports, baby sports, school sports, pregnancy sports, endurance sports, strength training, senior sports, television sports... This list is also an example of the efforts to systematically classify all sporting activities according to certain criteria (age, health status, performance).

Health can be defined in different ways. According to a salutogenic approach, it is more than the absence of disease or pain. It also encompasses the maintenance of cognitive abilities and emotional well-being. Cognitive abilities can be divided into many individual aspects, such as perception, attention, memory, problem-solving, language, and spatial intelligence. Emotional well-being can be distinguished between the emotional quality (e.g., frequency and intensity of joy) in current experiences and the more long-term evaluation of life (e.g., finding meaning). Numerous meta-analyses have already been conducted to determine which type of exercise or sport contributes particularly to positively influencing physical, emotional, and cognitive health in old age. For example, it has been shown that endurance interventions or strength training, or training that integrates endurance and strength, as well as Tai Chi, improve cognitive abilities in people over 50. The duration should be between 45 and 60 minutes, and physical training should be performed as frequently as possible. The results of this meta-analysis were independent of the cognitive status of the participants and the type of cognitive task (Northey, Cherbuin, Pumpa, Smee, & Ratray, 2018).

Karate – a motor and cognitive training

Based on these findings, we were particularly interested in whether multimodal athletic training, combining both cognitive and motor elements, can have a positive physical, cognitive, and emotional impact on older people. We decided to conduct a differentiated study of the influence of karate. The name "karate" is used for very different styles; our training adhered to the rules of the German Karate Association (DKV).

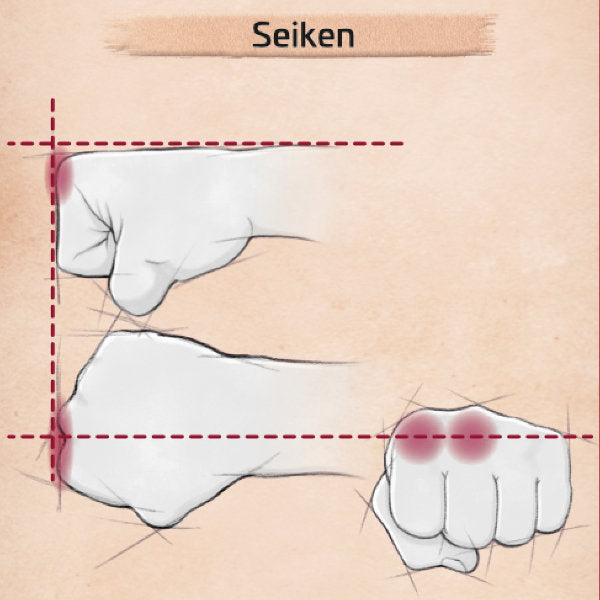

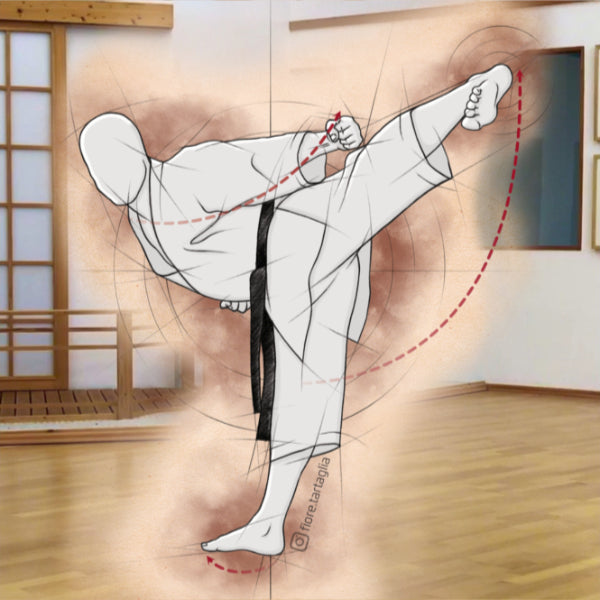

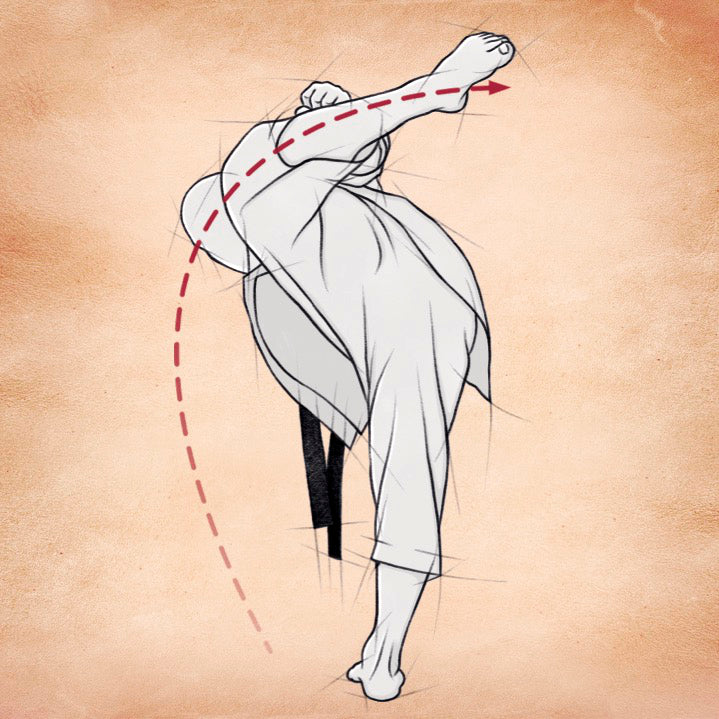

Translated, karate means "empty hand," originally "Chinese hand." It is a martial art that developed in Okinawa (part of the Ryukyu island chain, now part of Japan), heavily influenced by Chinese martial arts. Karate training was intended to enable the body and mind to withstand an attacker, even unarmed. The knowledge was passed on by masters to only a few select students. It wasn't until the early 20th century that karate first became known in Japan and later in the Western world. The training goals have since changed. In addition to using the martial art for self-defense and athletic competition, karate is also practiced as a health-promoting form of exercise and as a path (dō) to spiritual development ("meditation in movement"). Training takes place in groups. In the elementary school (kihon), forward and backward movements are practiced in combination with arm and leg techniques, such as punches and kicks. The speed and precision of the techniques, combined with the use of the entire body (hips), give the techniques their power. In partner training (kumite), attack and defense techniques are applied (with conscious mutual consideration), while in kata training, a sequence of up to 60 precisely prescribed hand and foot techniques, as well as turns in space, are performed. This "shadow fight" with an imaginary opponent places enormous demands on memory. (See Fig. 1 in the original article attached below) In the studies presented below, training was deliberately carried out without competitive ambitions and with the respect that is important for martial arts.

Our studies

In the first study on karate for seniors (Jansen & Dahmen-Zimmer, 2012), involving a total of 45 elderly people with an average age of 78.8 years (SD = 7.0), the effects of (DKV) karate training were compared with cognitive training and motor skills training. An additional control group received no intervention and only participated in the testing procedures. Cognitive performance was measured at the beginning and end of the intervention using various working memory tests, emotional well-being using a depression scale, and motor skills using a one-legged balance test. The motor skills training included light strengthening, mobilization, and stretching exercises. The cognitive training was based on a cognitive training program for older people, which primarily trains fluid intelligence and memory performance. The karate training was carried out as described, but with adjustments to the age group (e.g. no high kicks, sneakers allowed instead of barefoot, etc.) (See Fig. 2 in the original article attached below).

A total of 20 one-hour training sessions were offered per group on a weekly basis. The results showed no differences between the four groups regarding cognitive tests and balance, but a significant difference in the depression scale scores between the karate and control groups: While the depression score increased in the control group, it decreased in the karate group (see Figure 3 in the original article attached below).

Karate and mindfulness

Since karate contains elements of mindfulness, we decided to conduct a second study (Jansen, Dahmen-Zimmer, Kudielka, Schulz, 2017) to examine the effects of karate training compared to a mindfulness-only intervention. This randomized controlled trial examined the influence of (DKV) karate training compared to a mindfulness intervention and a control group in 55 adults with an average age of 63.5 years (SD = 5.7). Mindfulness describes the ability to perceive the current moment without judgment. The mindfulness group received a modified MBSR ( mindfulness-based stress reduction ) training program. This includes meditative exercises to achieve greater inner peace. For example, participants were guided to slowly and consciously perceive bodily sensations using a "body scan." The training sessions took place twice a week for one hour each time over a period of eight weeks.

Before and after the intervention, facets of cognition, emotional well-being, and chronic stress perception were measured. An additional hair cortisol measurement served as a physiological stress marker. The results showed an improvement in subjective health perception in the karate group and a reduction in anxiety in cognitive processing speed. The group that participated in the mindfulness intervention showed a reduction in stress perception (albeit only in trend). While no direct correlation was found between the physiological marker cortisol and the other measures, the higher the self-reported stress at the start of the intervention, the more pronounced the decrease in depression, anxiety, and stress scores.

Karate and dance for Parkinson's disease

In the third study (Dahmen-Zimmer & Jansen, 2017), we investigated the effects of (DKV) karate training and line dancing training on patients with Parkinson's disease. Parkinson's disease is a degenerative disease of the extrapyramidal motor system. It causes the death of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra . The motor symptoms include muscle tremors, muscle rigidity, slow movements (bradykinesia), a short-stepped gait, and postural instability. Cognitive decline and an increased incidence of depression can also accompany the motor symptoms.

In this study, we chose dance as a control group because, on the one hand, the motor demands are comparable and, on the other hand, several studies have already shown the beneficial effect of dance on motor parameters in patients with Parkinson's disease. Dance comes in many forms and styles - but ultimately it is always a movement in space to music, which can of course be very specific. The most internationally well-known dances include standard dances such as waltz, tango, samba and rock ' n ' roll; well-known dance styles include historical dances, folk dances, oriental dance and hip hop. The oldest surviving documentation of this - Indian cave paintings - date back to the period between 5000 and 2000 BC. It is undisputed that dance promotes the motor skills of endurance, strength and coordination, so that dance can also be regarded as a comprehensive form of athletic training.

Sixteen patients participated in karate training (mean age 68.9 years, SD = 7.2), and nine participated in dance training (mean age 72.3 years, SD = 6.7). Each training session took place once a week for one hour. A further control group, which received no intervention, comprised twelve participants (mean age 70.4 years, SD = 10.1). Emotional well-being, facets of cognition, and balance ability were assessed before and after the training phase. The results showed that balance improved significantly for both training groups (see Figure 4 in the original article attached below). This counteracts instability and the risk of falls.

The decrease in subjective emotional well-being (MDBF scale) that often accompanies the course of the disease continued only in the waiting control group, but significantly less in the karate and dance groups (see Fig. 5 in the original article attached below). The study shows that karate, like dance, can be successfully used as a potential motor intervention for patients with Parkinson's disease. This is, first and foremost, a feasibility study, and its results should be evaluated with caution.

Evaluation of the results

All three studies have shown that healthy older adults and also those with neurodegenerative diseases, such as patients with Parkinson's disease, can practice (DKV) karate. The demanding training had no harmful influence; on the contrary, it led to positive effects. Karate and dance significantly improved balance in Parkinson's patients, thereby counteracting postural instability. This can lead to a reduced fear of falling, which in turn can encourage patients to exercise more and be more active, which can promote or maintain social inclusion. A significant improvement in cognitive processing speed was observed when comparing karate with mindfulness training in healthy older adults; other cognitive parameters in the other studies showed no significant differences.

One possible reason for the reduction in depression scores after karate training (senior study) and the higher emotional well-being compared to the waiting control group (Parkinson's study) could be that the high level of concentration required during training prevents distraction by negative moods and brooding in the form of a "thought carousel." This is a mechanism of action that can also play a role in certain meditation techniques. Furthermore, self-efficacy expectations can be strengthened, that is, the belief in being able to overcome difficulties on one's own and in having achieved success thanks to one's own ability and effort. Older people and patients in particular often experience a loss of competence and independence. Learning and mastering demanding forms of movement and effective self-defense techniques can positively influence the experience of self-efficacy.

Critical reflection of research – between claim and reality

With our research, we are still at the beginning of a balancing act between scientific rigor and feasibility. In order to make reliable statements about the interaction of individual variables, psychological and sports science research uses experimental methods. In the simplest case, the change in the dependent variable (the outcome) is determined in relation to the variation in the independent variable (here, the intervention), keeping all other conditions constant. An important principle is randomization, i.e., the random distribution of participants among the different interventions. This ensures that the result is not influenced by an existing, unmeasured variable. According to the "pure doctrine" of scientific rigor, participants would have to be randomly (forced) assigned to a group. However, this would mean that the important factor of "personal choice of activity" would not be taken into account, making the training less attractive. On the other hand, if the desire to participate in a desired training is followed, the motivation of the participant will likely be increased, but the study would lose internal validity. In our research, we chose both an experimental approach (Karate – Mindfulness Study) and an application-oriented approach (Karate and Dance for Patients with Parkinson's Disease), each with its own advantages and disadvantages. In the study with Parkinson's patients, interested spouses and partners were also allowed to participate in the training (the data were not analyzed). This was in accordance with the wishes of the participating patients, but would have been impermissible under the desired experimental design.

This tension (scientificity versus feasibility) can be addressed with an experimental design, for example, by having participants participate in both interventions in a counterbalanced order or by randomly assigning them to the control group. However, this would increase the effort required by the participants (with the likelihood of a higher dropout rate) and also increase the time and costs. Ultimately, such a study can only be conducted with a larger team of researchers from the participating disciplines of medicine, psychology, and sports science. This collaboration would also facilitate the establishment of a standard for measuring cognitive, emotional, and physical health, which would allow many studies to be compared in the first place.

Does karate now offer a new remedy for movement disorders and for healthy aging? The initial study results are promising; many participants experienced improvements in mobility, health, and quality of life. The karate group (as well as the dance group) of patients with Parkinson's disease have continued training at their own request for two years after the study ended. Nevertheless, the studies must be understood for what they are—the beginning of an exciting research journey investigating the question of which type of exercise or sport can maintain holistic health in old age and during illness. Further research, also incorporating the possibilities of digitalization, is both meaningful and necessary.

The research project continues to have a very positive impact on the participating patients. Even two years after the project's completion, the Parkinson's patients are still regularly participating in karate training and have since passed their first exam (for yellow belt). In January 2020, Deutschlandfunk Kultur (Berlin) visited the training and reported on the project. The report can be heard here: https://ondemandmp3.dradio.de/file/dradio/2020/01/12/karate_fuer_parkinsonpatienten_positiv_fuer_die_motorik_drk_20200112_1738_19ed688f. mp3?fbclid=IwAR2OeMO3_dfIveBWf1l- rFpP-GZYyLL3E6zbx2HOgJ5dHiPidm0N-30jkKH-w

A report by BR Fernsehen about the study dates back to 2017: https://www.br.de/br-fernsehen/sendungen/gesundheit/parkinson-karate-regensburg100.html

literature

Joseph Michael Northey, Nicolas Cherbuin, Kate Lousie Pumpa, Disa Jane Smee, Ben Rattray, Exercise interventions for cognitive function in adults older than 50: a systematic review with meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine 52, pp. 154-160.

Petra Jansen, Katharina Dahmen-Zimmer, Effects of cognitive, motor, and karate training on cognitive functioning and emotional well-being of elderly people. Frontiers in Psychology: Movement Science and Sport Psychology 3 (2012), Article 40.

Petra Jansen, Katharina Dahmen-Zimmer, Brigitte Kudielka, Anja Schulz, Effects of karate training versus mindfulness training on emotional well-being and cognitive performance in later life. Research on Aging 39 (2017), pp. 1118–1144.

Katharina Dahmen-Zimmer, Petra Jansen, Karate and dance training to improve balance and stabilize mood in patients with Parkinson's disease: A feasibility study. Frontiers in Medicine: Geriatric Medicine 4 (2017), Article 237.

Katharina Dahmen-Zimmer, Petra Jansen, Karate and dance training to improve balance and mood stabilization in patients with Parkinson's disease: A feasibility study. Frontiers in Medicine: Geriatric Medicine (2017), 4:237. Doi: 10.2289/ fmed.2017.00237

The authors

Dr. Katharina Dahmen-Zimmer studied psychology at the Ruhr University Bochum and the Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf. She received her doctorate from the Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf in 1982. She worked as a research assistant at the University of Münster and then at the University of Regensburg in the field of experimental and applied psychology.

Research focuses on : In traffic psychology – information management, stress and strain on drivers. In sports psychology – the effects of exercise on older and/or disabled people.

Prof. Dr. Petra Jansen was appointed Chair of Sports Science at Regensburg University in October 2008. Previously, she was a senior academic at the Institute of General Psychology at Heinrich Heine University in Düsseldorf. Petra Jansen studied anthropology, psychology, ethnology, and mathematics at Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz. She earned her doctorate in general psychology on the cognition of distances from the University of Duisburg-Essen and completed her habilitation in experimental psychology on the development of spatial knowledge at Heinrich Heine University in Düsseldorf, conducting research in virtual environments. In Regensburg, she established the bachelor's program in Applied Movement Sciences and the master's program in Motion and Mindfulness .

Research focuses : Investigating the relationship between motor skills, cognition, and emotion; the importance of mindfulness on athletic performance and development throughout life. Further information can be found at https://www.uni-regensburg.de/psychologie-paedagogik-sport/sport-wissenschaft/forschung/puplikationen/index.html.

Here is the original article:

A recipe for healthy aging?